The cricketers for all ages

Engaging a cricket membership audience

MCC members choose their timeless cricketers

In a recent edition of MCC Magazine, we asked the members to select the cricketers from past and present that transcend the ages, whose skills and ability would have been recognised in any era. This is how they responded...

Nicholas ‘Felix’ Wanostrocht, 1830-1852

One of the greatest cricketers of the first half of the 19th century. An accomplished batsman, he scored over 4,000 runs, including a century and 15 fifties – no mean feat on the pitches of the time. He also bowled and took 113 catches. In addition to his prowess on the field he found time to write a text book on batting – Felix on the Bat - invent a bowling machine and, using India rubber for protection, the batting glove. He was also an accomplished writer and artist, documenting the nationwide tour by the All-England XI. Many of his original artworks are preserved in the MCC Collections. I should mention that Felix was my Great-great-great Grandfather, and we share the same birthday! Nominated by Michael C Nower

Editor says: Felix was an innovator and a thinker, an artist and a teacher. He was part of the All-England XI that took the professional game around the country and changed the landscape of cricket. I am sure he would have been a success in any era.

Sir Garfield Sobers, West Indies, 1954-1974

Garry Sobers would have been able to dominate in any of the modern forms of the game both as a batsman and bowler. As a batsman he was one of the greatest with the ability to score very quickly. As a bowler he could bowl fast and swing the ball, orthodox slow left arm or wrist spin. An unusually gifted cricketer. Nominated by Arthur Peirce/Norman Philpott

Editor says: Brilliant left-handed strokeplayer who broke the world Test record making 365* against Pakistan at the age of 21. Left-arm fast-medium bowler who also bowled chinamen or orthodox left-arm spin to Test standard. Six sixes in an over at Swansea. If there was an era of cricket Sobers couldn’t thrive in I wouldn’t like to see it.

Denis Compton, England, 1937-1957

Spinning the ball both ways is vital in one day cricket,” say the Sky pundits and this player did precisely that, earning over six hundred wickets by bowling chinamen and googlies whilst also scoring over a hundred centuries as a batsman. O’Reilly and Bedser were rated by Sir Don Bradman as the best bowlers he faced and our man scored centuries against both those peerless men on uncovered pitches; far harder to bat on than the modern equivalent. He needed to be fit when he played soccer, so he could adapt to cricket’s modern training methods though apparently his non-appearance for cricket pre-season practice was common. A tendency to absent-mindedness (e.g. to go to the wrong ground) would easily be overcome by the myriad of backroom staff loading his iPhone/iPad with ground directions, diary entries and dietary restrictions; whether he would remember to charge or switch on his gadget is a moot point. Finally, could he wear the baseball cap England players are now sewn into? No, his fine head of hair is probably still under contract to Brylcreem – a conundrum. Denis Compton still a man for all eras. Nominated by Simon Glyndwr John, Andrew Sargent, Michael Merrifield, Chris Barley

Editor says: Who could argue with Compton as a cricketer for all ages? Doubtful whether he could have carried on a dual football and cricket career in the modern era though.

Mansur Ali Khan Pataudi, India, 1957-1976

Nawab of Pataudi Junior, ‘Tiger’ Pataudi, is a whimsical choice. A hugely talented, unorthodox, stroke-playing young batsman, who broke Douglas Jardine’s batting records at Winchester College, moving on to become perhaps the last undergraduate to ‘fill’ The Parks at Oxford. Trevor Bailey, biographer of Sobers, rated the two young men as equal in talent. And then, aged 20, came that car accident and the effective loss of his right eye. Still 20, he made his Test debut, later captaining India at 21. The batting lost much of its exuberance but still brought six Test centuries. Other batsmen have needed to manage the likes of hayfever and epilepsy, but no other has even approached this level of Test success under such a handicap. Imagine judging length. No surprise that Pataudi was especially vulnerable at the start of an innings, as he adjusted. But this was an adaptable, resilient, thinking man, a charismatic unifier who transformed India with his use of a high-quality group of spinners and inspiring higher fielding standards, while providing core stability in a consistently weak batting line-up. Read Suresh Menon’s anthology of tributes for the reverence offered by so many fellow cricketers. Pataudi is a cricketer who would have excelled in any era. Nominated by John Reeve

Editor says: Pataudi Junior is one of the great ‘what ifs’ of cricket. Despite his visual impairment he averaged just a shade under 35 with the bat in Tests. His role as a captain was significant too; harnessing the gifts of a unique generation of talented spin bowlers to India’s great advantage. He was as visionary in this respect as Clive Lloyd was with West Indies a few years later.

Jacques Kallis, South Africa, 1993-2014

One of the great all-rounders surely in terms of his Test averages (batting: 55.37; bowling: 32.65) and in terms of the opposition he faced - Lara, Kumble, Warne, Sehwag, McGrath, Ponting, Sachin, Anderson, Murali, etc. Nominated by Frederick Price

Editor says: The pre-eminent all-rounder of his generation, some critics have argued that Kallis’s statistics are inflated by performances against weaker teams. His two lowest Test batting averages are against Australia and England, but both are over 40 and he scored 13 Test centuries against these opponents. Certainly bowling was the lesser of his suits but 291 Test and 269 ODI wickets indicate it was no weakness. Add to this 196 catches (mostly at slip) from 165 Tests and it would be hard not to accept that Kallis was to South Africa what Wally Hammond was to England in an earlier era.

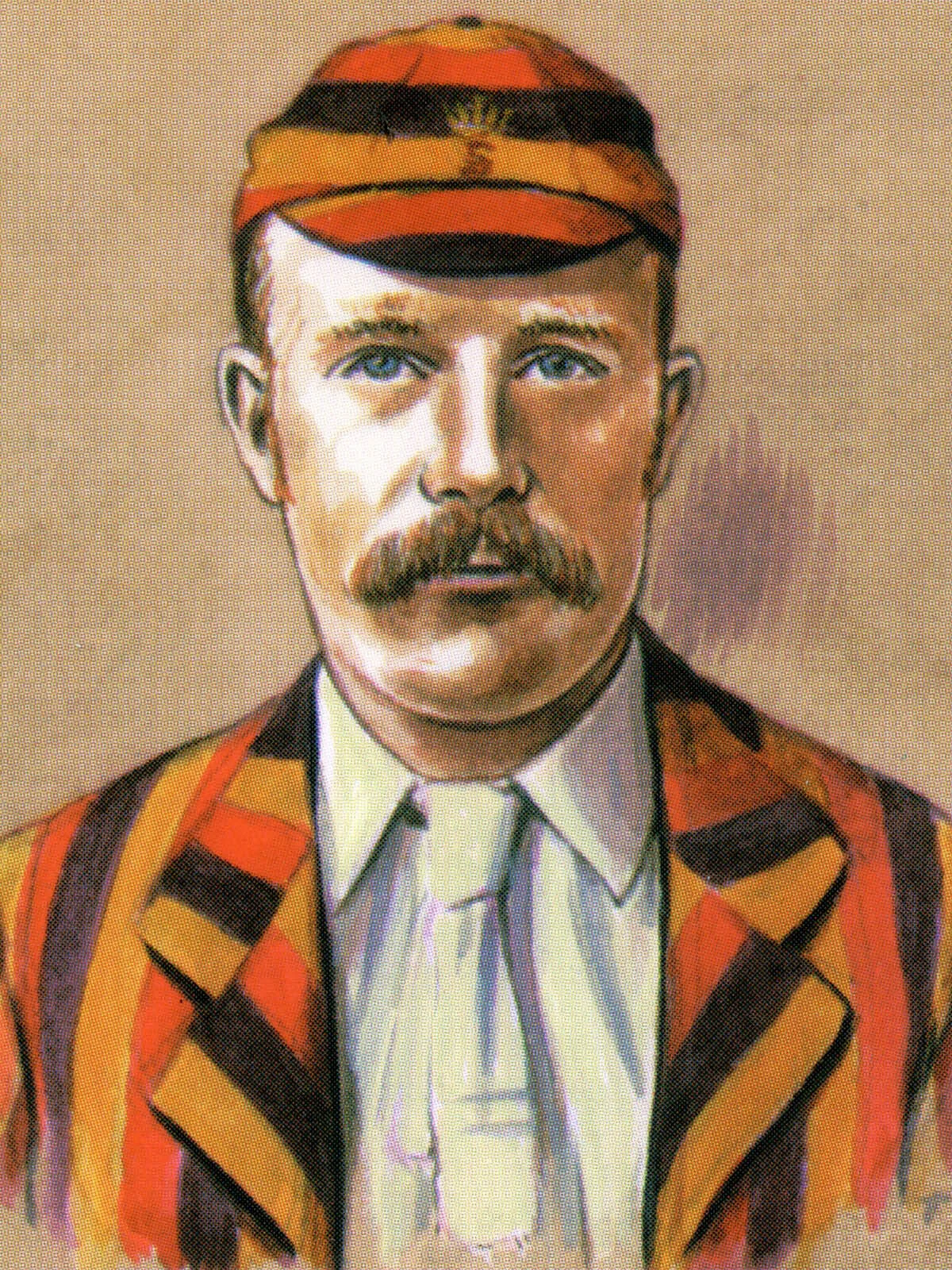

Bobby Peel, England, 1882-1899

Orthodox spin bowling is a department of the game which perhaps more than any other depends on the playing environment for its effectiveness and the exponent of it who seems to have best prevailed in conditions that did not help this bowling style, while lethal on those that did, was Bobby Peel, a Yorkshireman of the late Victorian era. No slow bowler in the game’s history has dismissed more Australian batsmen in Tests on their home turf, so often a finger spinner’s graveyard. Aside from his impressive bowling feats (including over 100 wickets for England costing under 17 runs apiece, figures that could have been even better but for Lord Hawke’s occasional refusal to release him from Yorkshire games for Test Matches), he was wholehearted in other departments of the game, being an excellent and tireless cover fielder and the best English professional left-handed bat of his time. Nominated by Hugh Faulkner

Editor says: Anyone ranked better than Wilfred Rhodes must be worth a second look. Bobby Peel’s statistics alone are remarkable: he twice took more than 20 wickets in a Test series in Australia and when in 1887-88 he only took nine, it’s fair to point out that he didn’t bowl much and took the nine at 6.44 each. The following summer he tormented the Australians on English turf, taking 24 wickets in just three Tests, including 7 for 31 at Old Trafford. So deadly was he with the ball he often opened the bowling for England. I had forgotten his batting but a highest first-class score of 210* for Yorkshire suggests he could look after himself in that department too.

Keith Miller, Australia, 1937-1959

The great Australian all-rounder of the 1940s and 50s – per Neville Cardus “the Australian in excelsis” and provider of the best quote in sporting history: “Pressure is having a Messerschmitt up your arse. Playing cricket is not”. Forerunner of Botham, Flintoff and Stokes, with a thousand times more style and panache. Nominated by Guy Beresford

Editor says: Think of Keith Miller and you think of verve, glamour and excitement. It is easy to forget the sheer cricketing achievement of the man in the light of that. Part of the famous Lindwall-Miller new ball axis that dominated England in the 1948 Test series, he averaged 57 with the bat in Shield cricket for New South Wales and 25 with the ball. He could inject surprising variety into his bowling, cutting and spinning the ball both ways if the situation required and his batting was more than just flair; seven Test centuries and several double-hundreds at first-class level indicate application as well as aggression.

Ben Hollioake, England, 1996-2002

On his ODI debut aged 19, Ben Hollioake was sent in at number three in a run-chase of 269 at Lord’s. He smashed 63 off 48 against the bowling of McGrath and Warne. He could hit a ball with enormous force which would have lit up the T20, yet he played with the elegance of cricketers past. With his sense of fun I imagine Ben would have loved The Hundred, embracing the fast pace of this new format. He never had time to truly cement his place in the Test team but showed the ability to come in down the order and bat diligently when required. Sadly we will never know quite what Ben would have gone on to achieve. Nominated by Clare Adams

Editor says: I was lucky enough to see Ben Hollioake’s final first-class innings at The Oval in September 2001. He hadn’t played Test cricket for three years and his career seemed to have stalled, but there were good signs that summer and that late summer day at The Oval he came in at number seven, and put on 215 with Mark Ramprakash against a decent Yorkshire attack led by Matthew Hoggard. Ben’s innings of 118 showed a new maturity, with all of the elegance Clare remembers still intact. It was an innings that suggested things had really clicked with this, still young, cricketer and promised great things for the future. Sadly not to be.

EDITOR’S PICK

Sydney Francis Barnes (1894-1930)

How can we be sure that a cricketer, master in his or her own era, would have been equally masterful in any other? Is it a question of sheer dominance, as with Bradman, or flair as with Compton or Miller? Surely adaptability has to come into it. A batsman such as Jack Hobbs, for instance, renowned for his skill in all conditions, would obviously be a strong candidate. Perhaps it is more obvious with batsmen; it would be hard to imagine Geoffrey Boycott thriving in the unorthodox world of Twenty20. Denis Compton would naturally have loved it. For a bowler, surely the main criterion must be adaptability; the skill to use varied conditions to their advantage, to restrict scoring as effectively as they take wickets.

Few bowlers in history have been as adaptable, or as successful, as Sydney Barnes. He began his first-class career with Warwickshire before moving to Lancashire in 1899, but after 1903 he played no more first-class county cricket, concentrating instead on minor counties cricket with Staffordshire and Lancashire league cricket with four different teams. Uniquely in cricket history, Barnes played more Test cricket for England after he had abandoned the County Championship; 23 of his 27 Test Matches came after this point. In all, he took 189 Test wickets at an average of 16.43. Two hundred and seventy Lancashire league matches brought him 1,050 wickets at 8.92. In 133 first-class matches he claimed five wickets no fewer than 68 times.

But the brilliance of Barnes goes way beyond statistics. For a start there was his longevity: he was still playing for Staffordshire in 1935 at the age of 62. His career spanned the era of Grace and that of Bradman. That alone for a bowler is remarkable. Then there was his style. It was every style. Fast-medium outswing, inswing, off-break, leg-break, top-spinners. He was said to have bowled a hard-spinning leg-break faster than anyone before or since – Neville Cardus christened it the ‘Barnes ball’ – and it was a ball genuinely spun from his strong fingers, not cut or rolled. He kept his wrist straight, spinning from the front of the hand, which allowed him to maintain his pace and control and made it difficult for the batsman to anticipate which way the ball might turn. A master too of psychology, often knowing where the batsman would try to hit the ball before the batsman himself. Tall, lean, stern-faced, extracting bounce and spin from the most unhelpful surface, it is hard not to think of him as Glenn McGrath and Shane Warne rolled into one. Famously stubborn and taciturn, he is said to have mellowed in later life. But that was after he stopped playing cricket.